Women process palm oil in the remote, off-grid village of Aseigbo, in Nigeria’s Ondo state. Photo credit: Naomi Mihara, Devex.

Women process palm oil in the remote, off-grid village of Aseigbo, in Nigeria’s Ondo state. Photo credit: Naomi Mihara, Devex.

ABUJA, Nigeria — It takes nearly an hour to drive from Akure, the Nigerian capital of Ondo state, to the remote, palm-flecked village of Aseigbo. That’s on a clear day. During the wet season, the narrow dirt road leading to the village turns to churning mud, virtually cutting off the small community from the outside world for months at a time, until the season changes and the ground dries. Phones don’t work here; it’s outside the range of any cell tower. Nor do most homes have electricity or indoor plumbing. In case of emergency, or an outbreak of disease, it might take the central authorities weeks — or even months — to mobilize a proper response.

At least, that’s how things worked before the satellite receptors came. Today, thanks to a new partnership, not only is Aseigbo on grid — allowing local health care workers to contact central authorities at the touch of a button — but they are able to record patients’ health data via tablet, which can immediately be uploaded to a cloud. In a country where the vast majority of health data are still recorded by hand on registries, if taken to scale the project has the potential to revolutionize health coverage in Nigeria.

More on the partnership

The International Partnership Program project between U.K.-based commercial satellite operator Inmarsat, social enterprise InStrat Global Health Solutions, and public authorities in Ondo state, is funded by the UK Space Agency, with the aim of tackling health care challenges with satellite communications technology.

For more information about the IPP, visit the official website.

When people think about the many applications of satellite technology, improving health care delivery in the developing world is probably not the first thing that comes to mind. But the new International Partnership Program aims to do just that. By combining satellite networks with tablet technology, the project partners hope to launch Nigeria’s health system into the modern digital world.

Harness the power of big data

Despite boasting the biggest economy in Africa, Nigeria faces formidable health challenges: A 2017 UNICEF report found the country to have the third-highest infant mortality rate in the world. One major contributing factor is a human resource gap. The World Health Organization identified Nigeria as one of 57 countries with a critical shortage of health care workers, far fewer than the threshold of 2.3 doctors, nurses or midwives per 1,000 people to ensure minimal access to health care for all.

Nigeria’s health information system is also primarily paper-based — which means that before a patient can be treated, their data need to be recorded on paper rosters then transferred by hand from one health care provider to another. It’s a system that can lead to significant delays and data loss — particularly when patients are referred to secondary or tertiary health care facilities.

Looking at these challenges gave Nigerian diaspora professional Okey Okuzu an idea. Formerly the director of strategy and innovation at pharmaceutical giant Novartis, Okuzu had managed projects that used big data to improve health care delivery.

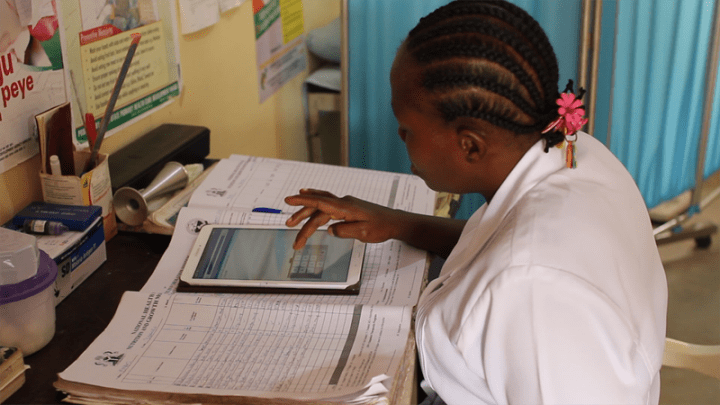

Yemisi Olorunemojutimi, a community health extension worker in Aseigbo village, enters patient data into the CliniPAK online system.

Yemisi Olorunemojutimi, a community health extension worker in Aseigbo village, enters patient data into the CliniPAK online system.

“I started to think, what if we could take this system-design thinking and bring it into Africa, in Nigeria, and begin to design things that could make systemic impact in health care delivery?”

Inspired by this thought, he founded InStrat Healthcare Solutions in 2010. Initial pilots relied on mobile phones and SMS technology, however he felt that SMS technology would soon become obsolete and subsequently worked with a VecnaCares Charitable Trust to customize its newly developed health management application, CliniPAK, for the Nigerian context. This interaction led to the mobile version of CliniPAK, which can be run on tablet computers.

The idea behind CliniPAK is a simple one: Health workers record individual patient information directly on the app, which is delivered in real time via the cloud to remote servers, where the information is aggregated and delivered to state health authorities. This solves two problems at once. Government officials have access to extremely accurate data at the local, regional, and national levels on which to base policy decisions. Patient care also improves, by ensuring that workers mostly at primary health facilities have immediate access to patient data, rather than having to wait for paper records to be transferred by hand.

While a great idea in theory, they almost immediately ran into challenges, for example a lack of 3G connectivity. “Before we started working, the first thing we would do is take a smart device, turn it on, and see if there was network or not,” Okuzu said. “If there was no cellphone network, we’d put an ‘X’ over that facility, and we couldn’t work there.” In practice, that meant that roughly one-third of Nigeria’s 30,000 facilities were off limits.

That’s where the satellites came in: By installing satellite receptors powered via solar panels in remote villages in rural Nigeria, they were able to provide network coverage to villages without electricity or running water.

“Working with the UK Space Agency and Inmarsat, we’ve been able to go into those places which arguably is where the need is most dire, because they are the most remote places,” he said. “And we’ve been able to allow them to reap the benefits that we bring with modern mobile technology.”

Satellites for survival: Saving lives in Nigeria Video trainings to address the human-resource gap, and save lives

CliniPAK was an immediate hit with health care workers who no longer had to spend hours each day transferring patient health data from one roster to another, or days every month carrying copies of the rosters to public health authorities for verification.

But it soon became apparent that health care workers had other unaddressed needs. Along the way, they found out that the health workers that were responsible for managing the health data weren’t being trained, said Okuzu.

“They were in such rural places that there wasn’t a critical mass of them in any one health care facility [and] that it made sense for the government to send trainers,” he added. “We recognized that on this same device that we were using to capture patient data, we could put in an application and deliver training on that same application.”

Get development's most important headlines in your inbox every day.

No comments:

Post a Comment